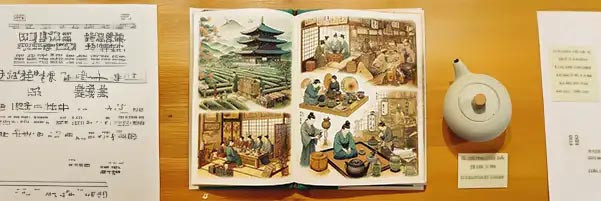

The Japanese tea ceremony, also known as Chanoyu or Sado, is a Japanese cultural practice that dates back over 800 years. It was introduced to Japan by Buddhist monks who discovered it during their travels to China.

Origins and evolution of the tea ceremony in Japan:

The tea ceremony, known as chanoyu or sado in Japanese, is a cultural practice deeply rooted in Japanese tradition. It is considered one of the most refined and elegant forms of Japanese art, and has been celebrated for centuries.

Origins of the tea ceremony

The origins of the tea ceremony date back to the late 12th century, when the Buddhist monk Eisai brought tea seeds from China to Japan. These seeds were planted in the Kennin-ji temple in Kyoto, where Eisai began teaching the virtues of tea to his disciples.

Over time, tea became a popular beverage in Japan, and nobles began to hold tea ceremonies in their palaces and residences. However, it was not until later, in the 16th century, that the tea ceremony as we know it today took shape.

The evolution of the tea ceremony

The Japanese tea ceremony was largely influenced by the teachings of Zen monk Myōan Eisai, who introduced the practice of tea to the country. However, it was Sen no Rikyū, a nobleman and tea master, who truly shaped the tea ceremony as we know it today.

Sen no Rikyū developed a minimalist approach to the tea ceremony, known as wabi-sabi, which emphasized simplicity and the beauty of imperfection. This approach influenced many other aspects of Japanese culture, including architecture, ceramics and calligraphy.

Over time, different styles of tea ceremony have emerged, each with their own approach and philosophy. The three main schools of tea ceremony in Japan are Urasenke, Omotesenke and Mushanokojisenke, each with their own style and traditions.

Today, the tea ceremony is still an important cultural practice in Japan, with many followers and many schools continuing the tradition. It has also become popular around the world, with many tea enthusiasts studying the ceremony and hosting events to practice it.

The different trends of the tea ceremony:

There are several streams of tea ceremony in Japan, each with its own philosophy and style. The three best known currents are:

The Omotesenke Current

The Omotesenke stream is one of the three main schools of Japanese tea ceremony, the other two being Urasenke and Mushakōjisenke. Founded in 1665 by Sen Sōshitsu, the great-son-in-law of Sen no Rikyū, the founder of the Japanese tea ceremony, the Omotesenke school has since developed its own aesthetic and philosophy of tea ceremony.

Omotesenke emphasizes simplicity and natural beauty, seeking to create a calm and soothing environment for tea ceremony guests. The participants' gestures and movements are slow and precise, and each element of the ceremony, from bowls to utensils, is carefully chosen to create aesthetic harmony.

One of the key elements of the Omotesenke tea ceremony is the use of wagashi, traditional Japanese sweets, to accompany the tea. These sweets are often made from glutinous rice, red bean paste or sugar, and are designed to complement the flavor of the tea and enhance the taste experience of the ceremony.

The Omotesenke school has also developed its own range of tea bowls and utensils, which are often handmade by skilled artisans. These objects are considered works of art in themselves, and are often displayed in museums and art galleries.

Today, the Omotesenke school is one of the most popular and respected tea ceremony schools in Japan and around the world. His teachings have been passed down from generation to generation, and continue to influence the practice of the tea ceremony and Japanese culture in general.

L'Omotesenke met l'accent sur la simplicité et la beauté naturelle, cherchant à créer un environnement calme et apaisant pour les invités de la cérémonie du thé. Les gestes et les mouvements des participants sont lents et précis, et chaque élément de la cérémonie, des bols aux ustensiles, est soigneusement choisi pour créer une harmonie esthétique.

L'un des éléments clés de la cérémonie du thé Omotesenke est l'utilisation de wagashi, des confiseries traditionnelles japonaises, pour accompagner le thé. Ces sucreries sont souvent faites à partir de riz gluant, de pâte de haricots rouges ou de sucre, et sont conçues pour compléter la saveur du thé et renforcer l'expérience gustative de la cérémonie.

L'école Omotesenke a également développé sa propre gamme de bols et d'ustensiles de thé, qui sont souvent fabriqués à la main par des artisans qualifiés. Ces objets sont considérés comme des œuvres d'art en eux-mêmes, et sont souvent exposés dans des musées et des galeries d'art.

Aujourd'hui, l'école Omotesenke est l'une des écoles de cérémonie du thé les plus populaires et les plus respectées au Japon et dans le monde entier. Ses enseignements ont été transmis de génération en génération, et continuent d'influencer la pratique de la cérémonie du thé et la culture japonaise en général.

Urasenke school

The Urasenke School is one of the three main schools of Japanese tea ceremony, along with the Omotesenke School and the Mushanokojisenke School. Founded in the 17th century by Takeno Jōō, a disciple of Sen no Rikyū, the Urasenke school is the most popular and influential school today.

The Urasenke movement is known for its approach to the tea ceremony, which emphasizes harmony, mutual respect and simplicity. Practitioners of the Urasenke School are encouraged to create an environment of serenity and peace, using simple and elegant gestures to prepare and serve tea.

An important aspect of the Urasenke school's approach is the emphasis placed on observing nature and the season. The objects used for the tea ceremony are carefully chosen to reflect the mood and atmosphere of the current season, using specific colors, patterns and materials to create a harmonious environment.

The Urasenke School also encourages practitioners to develop their own style of tea ceremony, drawing on the school's core principles to create a unique and personal experience. Students are encouraged to study the teachings of the school's great masters, while exploring their own creativity and personal sensitivity.

Today, the Urasenke school is represented in many countries around the world, and continues to inspire tea ceremony practitioners through its elegant and refined approach to this ancient and venerable practice.

The Mushanokojisenke current

The Mushanokojisenke school is one of the three main schools of Japanese tea ceremony, the other two being Urasenke and Omotesenke. This school is often considered the oldest of the three and has a rich history dating back to the 16th century.

The Mushanokojisenke school was founded by Mushanokoji Saneatsu, a disciple of Sen no Rikyū, the founder of the Japanese tea ceremony. Saneatsu developed his own style of tea ceremony, which was influenced by the Zen Buddhist tradition. This approach gave rise to a simpler, more austere style of ceremony, which was very influential in the development of the tea ceremony in Japan.

The Mushanokojisenke style of ceremony is known for its elegance and simplicity, with an emphasis on respecting nature and celebrating the beauty of imperfection. The bowls and utensils used in the tea ceremony are often chosen for their simplicity and rusticity, and the decoration of the tea room is often minimalist, emphasizing natural elements such as flowers and tree branches.

Today, the Mushanokojisenke school continues to carry on the tradition of the Japanese tea ceremony, training new disciples and holding ceremonies for the general public. Followers of this school continue to seek harmony with nature and celebrate the beauty of the present moment, following the teachings of their masters and ancestors.

The great masters of the tea ceremony:

The Japanese tea ceremony has produced many great masters over the centuries, who have left their mark on the history of this practice. The three most famous are:

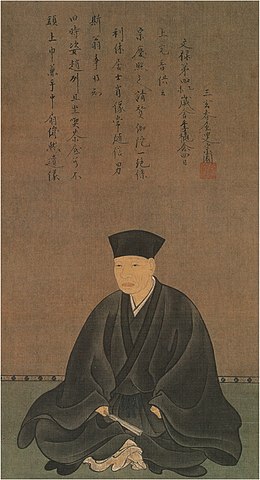

Sen no Rikyū

Sen no Rikyū (千利休) (1522-1591) is considered one of the greatest masters of the Japanese tea ceremony. He revolutionized the art of the tea ceremony by introducing the principles of simplicity, austerity and rusticity into the practice, in opposition to the more elaborate styles of the time. Born into a merchant family in Sakai, Rikyū became a disciple of Takeno Jōō, a tea ceremony master of the time, at the age of seventeen. He later studied with other important masters of ceremonies, such as Kitamuki Dōchin and Takeno Shigeharu, and developed his own style of ceremony, which later became known as the "Rikyū style". Rikyū also worked as an advisor to shogun Toyotomi Hideyoshi, who greatly enjoyed his tea ceremony. However, their relationship deteriorated after Rikyū refused to follow Hideyoshi's orders regarding the construction of the Taian tea house. Rikyū was forced to withdraw from public life and, ultimately, he was forced to commit suicide on Hideyoshi's orders. Despite his tragic end, Sen no Rikyū left a lasting mark on the art of tea ceremony and is considered an undisputed master in the field. His influence is still visible today, and many aspects of the tea ceremony, such as the importance of simplicity and rusticity, were directly influenced by his teachings.

Kobori Enshu

Kobori Enshu (1579-1647) was a Japanese tea master, artist and architect who greatly influenced the culture of the Edo period. Born into a samurai family, Enshu was introduced to the tea ceremony at a young age. He quickly developed a great interest in arts and culture, and became an expert in many fields, such as architecture, calligraphy, poetry and painting. Enshu is best known for his contributions to the tea ceremony, which he greatly modified and simplified. He also designed many tea gardens and introduced innovations in the construction of tea rooms. As an architect, he worked on numerous projects, including the renovation of several imperial temples and palaces. In addition to his artistic work, Enshu was also a tea connoisseur and a successful merchant. He traveled all over Japan to purchase the finest teas and rarest tea accessories. He also developed expertise in growing tea plants and producing tea, contributing to the expansion of the tea industry in Japan. Today, Kobori Enshu is considered one of the greatest tea masters of all time and is still honored for his contributions to Japanese culture. His philosophy of wabi-sabi, which encourages simplicity, rusticity and harmony with nature, continues to influence the tea ceremony and art in general.

Imai Sōkyū

Imai Sōkyū (今井宗久) was a famous Japanese tea master of the Urasenke school, one of the three major schools of Japanese tea ceremony. Born in 1520 in Kyoto, Sōkyū began studying the tea ceremony under the tutelage of master Takeno Jōō, a student of Sen no Rikyū, the founder of the Japanese tea ceremony. Sōkyū developed his own style of tea ceremony, which was known for its refinement and simplicity. He also taught the tea ceremony to many disciples, who later founded their own schools. During his life, Sōkyū was also active in politics, serving on several occasions as an advisor to the Tokugawa shogunate. However, he always maintained his passion for the tea ceremony and continued to teach and practice the ceremony until his death in 1591. Today, the Japanese tea ceremony is still practiced around the world, and the influence of masters like Imai Sōkyū continues to be felt in the practices and traditions associated with this ancient and refined practice. Sōkyū a développé son propre style de cérémonie du thé, qui était connu pour son raffinement et sa simplicité. Il a également enseigné la cérémonie du thé à de nombreux disciples, qui ont ensuite fondé leurs propres écoles. Au cours de sa vie, Sōkyū a également été actif en politique, servant à plusieurs reprises comme conseiller auprès du shogunat Tokugawa. Cependant, il a toujours maintenu sa passion pour la cérémonie du thé et a continué à enseigner et à pratiquer la cérémonie jusqu'à sa mort en 1591. Aujourd'hui, la cérémonie du thé japonaise est toujours pratiquée dans le monde entier, et l'influence de maîtres comme Imai Sōkyū continue d'être ressentie dans les pratiques et les traditions associées à cette pratique ancienne et raffinée.